Surprising Stories: Joséphine’s Black Swans

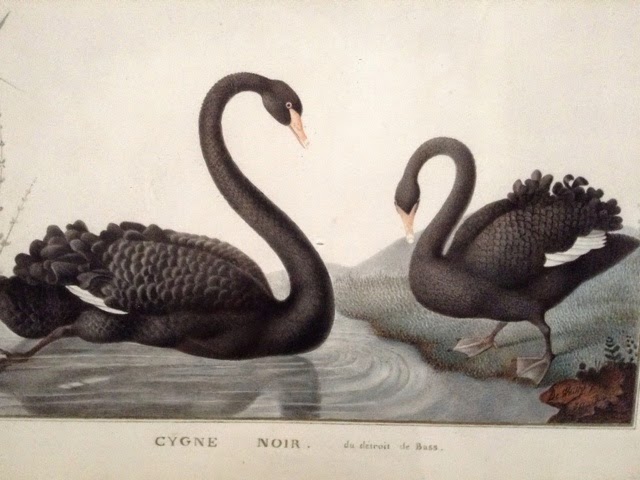

Title page, Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes Vol 3. Black swans, kangaroos and dwarf emus all frolic in the splendid gardens of Malmaison

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in his pioneering book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2010), referred to the bird as a metaphor for understanding unpredictability, arguing that “black swans” are events that come as a surprise, undermine common knowledge, and are often rationalized after the fact. In today’s world, COVID-19 can be considered a black swan. As Taleb writes: “A small number of black swans explains almost everything in our world, from the success of ideas and religions, to the dynamics of historical events, to elements of our own personal lives.” It is within this context that we are launching our new series, Surprising Stories, featuring intriguing aspects of French history and culture. We start by starting with the little known topic of Joséphine Bonaparte and her black swans.

Black Swans at Malmaison. Image: rmngp

Today we know that black swans are not metaphorical beasts, but chenopis atrata birds native to Australia. Perhaps less well known is the fact that Joséphine Bonaparte was the first to acclimate black swans at her Malmaison garden. In 1800, the navy captain, adventurier and explorer Nicholas Baudin appealed to Napoleon Bonaparte and the scientists at the national botanical garden, the Jardin des Plantes, to underwrite his exploratory voyage to what was then called New Holland.

Black swans at Malmaison

Baudin’s request was granted, allowing him to embark on a journey to the Pacific. Joséphine helped to underwrite the voyage and requested that the most amazing discoveries be brought directly to her at Malmaison. Despite incredible odds, Baudon returned to Le Havre in June 1803 with male and female black swans, along with other birds, kangaroos and emus that survived the voyage on the ship the Naturalist. As promised the swans found a new home at Malmaison and lived for the next ten years. Contemporary engravings show them near the river and roaming the lawns of her vast estate that included hot houses, a menagerie and sheep farm.

Armchair Joséphine by Jacob. Photo: Jebulon / Musée de Malmaison

Why did Joséphine lay claim to black swans? Since antiquity, swans were symbols of grace and beauty, sacred to Aphrodite and Apollo. Joséphine adopted the swan as her personal symbol, a sign of her own beauty, grace and seductive power. She commissioned swan motifs on decorative arts, chairs, and fabrics, including the famous Imperial swan arm chair.

Today at Malmaison, a family of black swans, not the friendliest of birds, continue to live on the property.

You may like to watch this beautiful video about Malmaison by Secrets d’Histoire (originally posted here). It features Joséphine’s black swans and provides a lovely virtual view into the castle and estate.

You can also learn more about this topic in my article Joséphine at Malmaison: Acclimatizing Self and Other in the Garden for Journal 18 or in person on our private excursions to the Château de Malmaison. Read more about this half-day excursion from Paris here and peruse our full range of tours at this link.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!