https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gingerbread-christmas-decoration-food-biscuit-bredele-tree-1617221-pxhere.com_.jpg

900

1350

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-12-10 11:37:342024-12-10 11:41:05The Best Traditional French Holiday Treats

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/qi-li-ORsHmchc3x4-unsplash-scaled.jpg

1920

2560

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-11-21 11:47:222024-11-22 10:13:31Notre Dame de Paris: A Glorious Restoration and Reopening

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-13-at-11.14.23.png

606

830

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-09-13 15:52:042024-09-18 14:28:28Surprising Story: Nélie Jacquemart-André and the Chaalis Abbey

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Mont-Saint-Michel_vu_du_ciel.jpg

1440

2560

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-03-25 18:33:102024-06-21 11:30:45Surprising Story: Mont-Saint-Michel and its Bay

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Rambouillet-grotto-2-scaled.jpg

2560

2384

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-03-07 10:00:332024-03-10 16:44:56Surprising Story: Marie-Antoinette's Dairy at Rambouillet

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/1788-portrait-of-the-princess-of-lamballe-by-anton-hickel-at-the-liechtenstein-b51fde.jpg

840

679

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002024-03-07 08:56:142024-03-25 18:01:17Surprising Story: The Princess de Lamballe at Rambouillet

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/10c92f9e-6941-4741-884d-0e6dc954154d.jpg

1280

1280

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

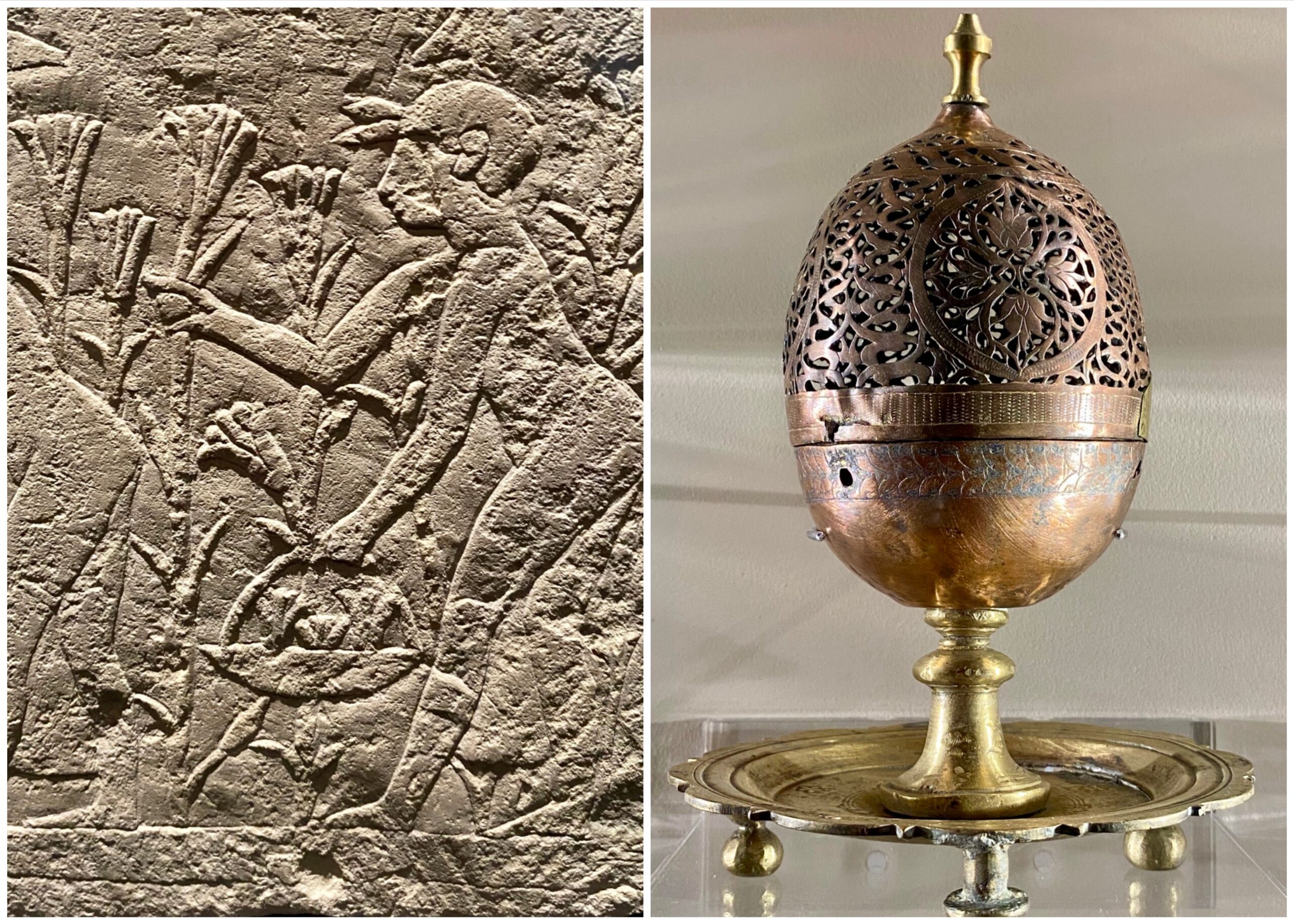

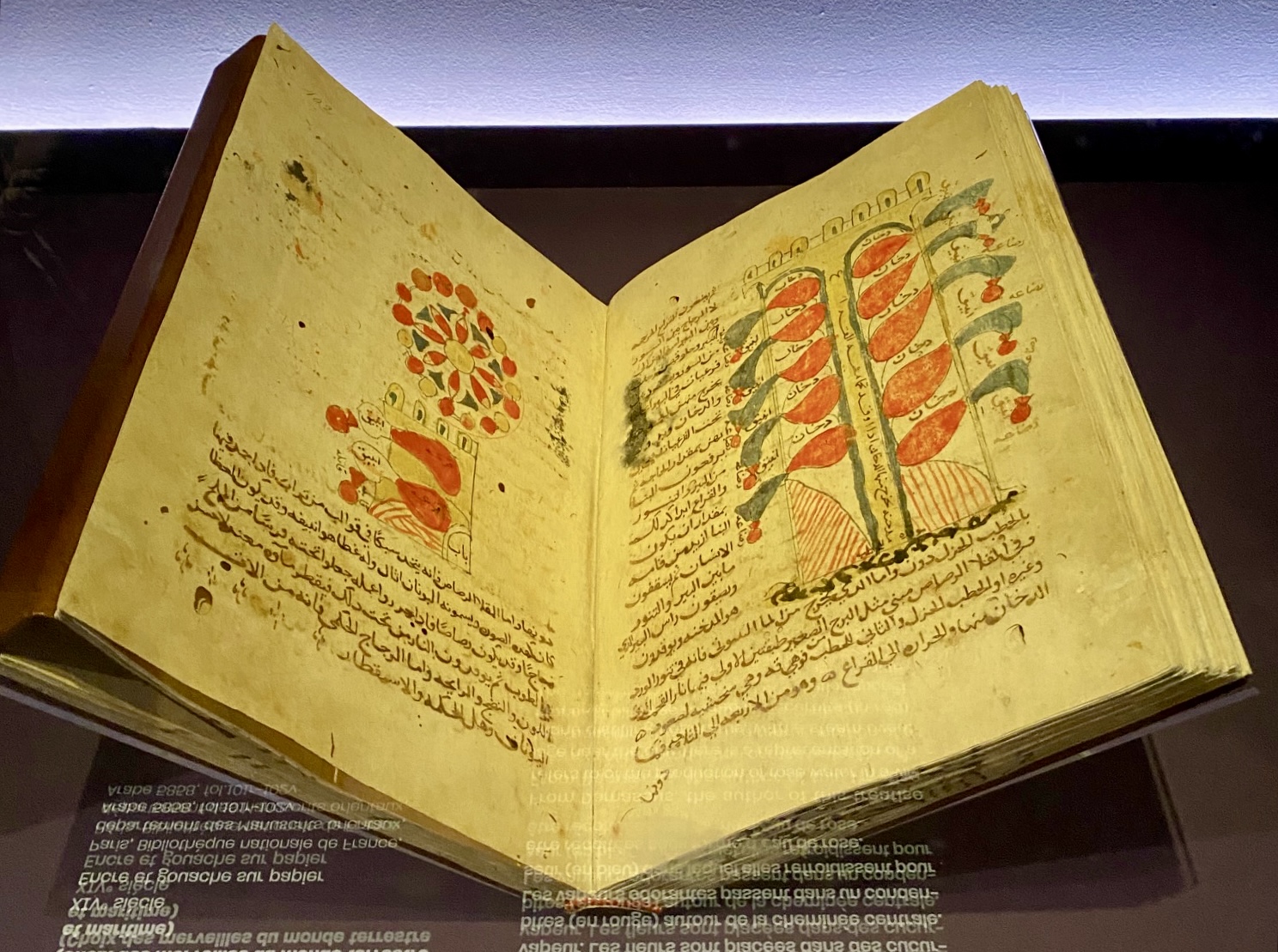

admin88002023-11-22 10:09:382023-11-26 09:21:25Perfumes of the Orient Exhibit, a Evocative Journey through Scent

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/263808352_4477461645623970_5561629971198846003_n.jpg

1440

1440

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002023-11-13 18:19:482023-11-26 09:24:46Chestnuts, a French Wintertime and Festive Season Essential

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/1647px-LEmbarquement_pour_Cythere_by_Antoine_Watteau_from_C2RMF_retouched.jpg

1080

1647

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

admin88002023-09-21 11:44:472023-09-21 13:20:26Autumn 2023: a Season of 18th Century Exhibits

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Screenshot-2023-09-21-at-10.57.24.png

1072

1242

admin8800

https://www.picturesquevoyages.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/picturesquevoyageslogo-300x68-2-300x68.png

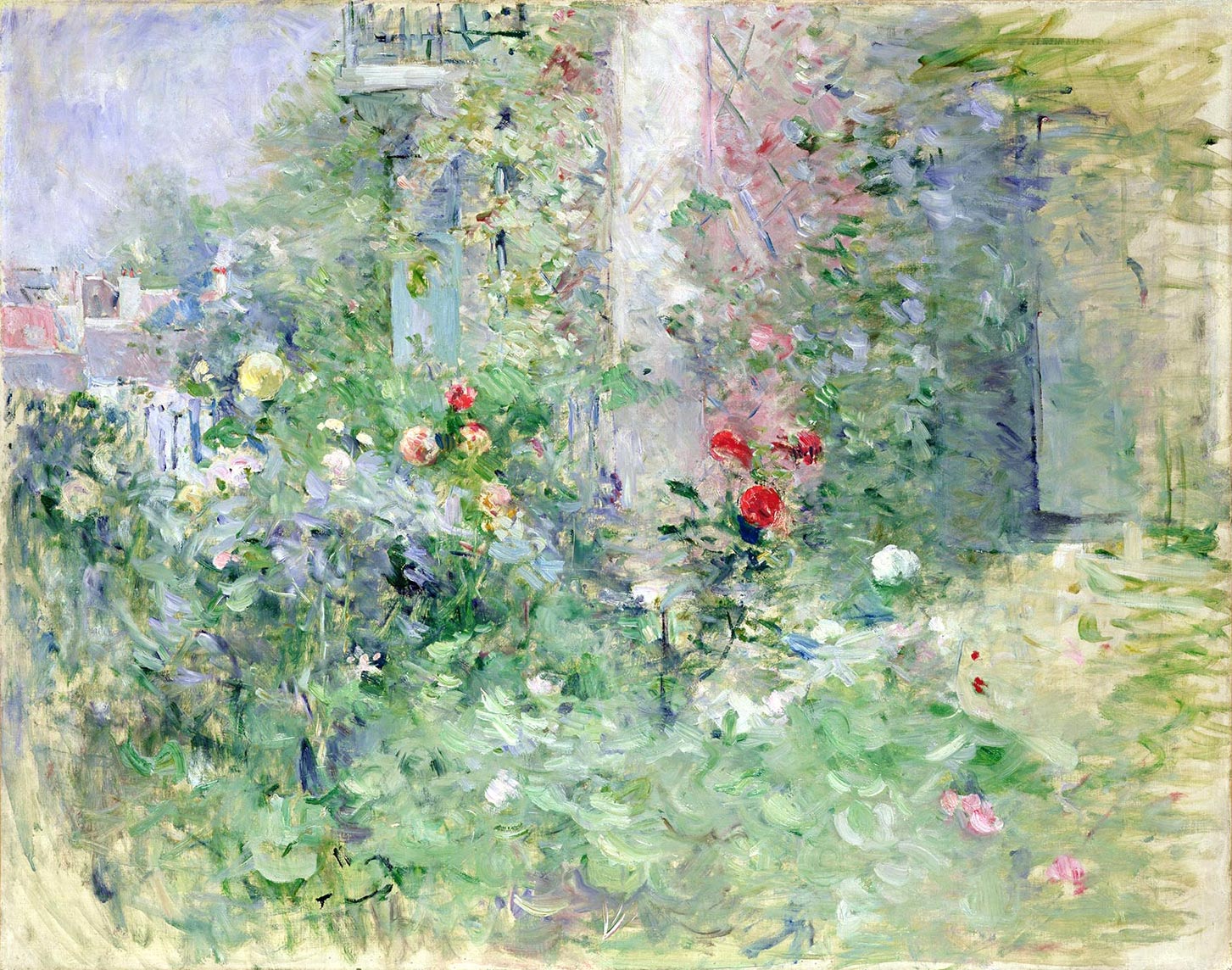

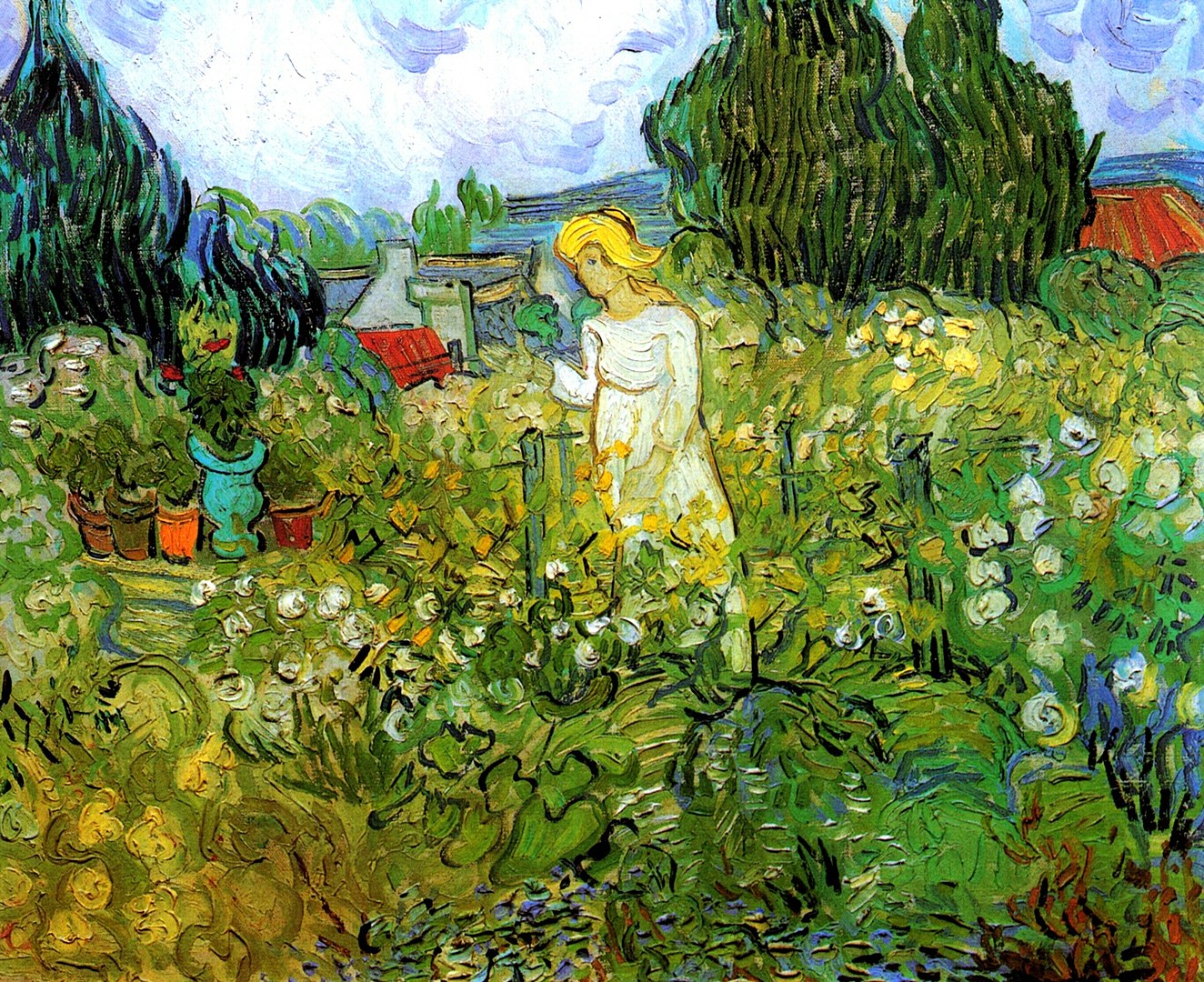

admin88002023-09-21 11:03:172023-09-23 11:28:05Vincent Van Gogh and Flowers

Scroll to top

There are many reasons to come to Paris for Christmas. Streets are decked out in beautiful lights (such as the Champs Elysées), chateaux host special holiday events (like Vaux-le-Vicomte), but one of the best reasons is the food. Although the French take gastronomy very seriously all year round, cuisine plays an even greater role over the festive season, especially when it comes to holiday treats. Specialties can vary from region to region, while others have spread around the whole country. Whether you’ll be in France over the holidays or would like to try some new recipes back home, here are some of the best traditional French Christmas treats. Read more

There are many reasons to come to Paris for Christmas. Streets are decked out in beautiful lights (such as the Champs Elysées), chateaux host special holiday events (like Vaux-le-Vicomte), but one of the best reasons is the food. Although the French take gastronomy very seriously all year round, cuisine plays an even greater role over the festive season, especially when it comes to holiday treats. Specialties can vary from region to region, while others have spread around the whole country. Whether you’ll be in France over the holidays or would like to try some new recipes back home, here are some of the best traditional French Christmas treats. Read more